A love letter to living, noticing, and feeling

Meaning and the present moment ☕️

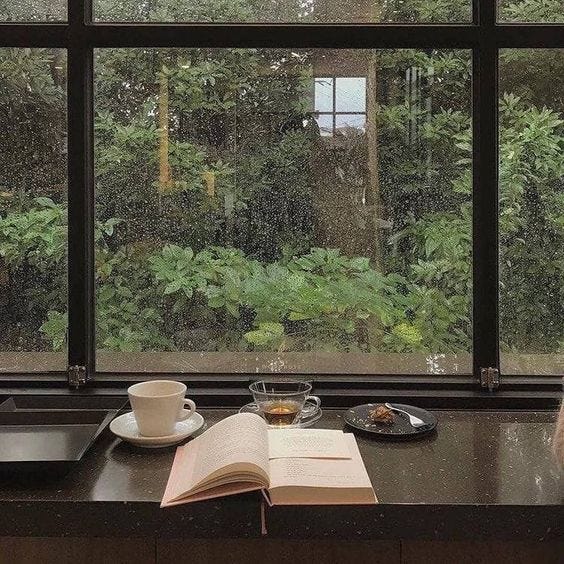

Every morning when I’m at my house in Athens, I finish my breakfast and I pour myself some of our famous filter coffee. It’s by a small Greek brand, with a hint of cinnamon added by my mom in the filter (before the coffee), and a smell of coffee and hazelnut that’s among the best things you’ll ever smell, guaranteed. Friends that are frequent and observant visitors always associate this scent with our house, and it’s true, it wouldn’t be a home without it. When my friend came over one day and said “please tell me you have some of your usual coffee”, I felt an inexplicable spark of joy.

My mom always makes the coffee first thing in the morning, and I’m drinking it while writing this even though it’s gone cold. No matter what, the coffee is in the pot. And every single morning I wait until I finish my breakfast first to pour it, because I want coffee and breakfast to be two different exciting moments in my day. And every single morning, I get so excited at pouring the coffee- you might even argue I feel more strongly about pouring it than drinking it.

The consistency of my love for this coffee and its reliable presence in the pot is important to me, and here’s why. This week I’ve been reading Albert Camus: I started with L’Étranger (The Stranger / The Outsider), and continued with The Myth of Sisyphus (an essay on his absurdist philosophy). I enjoyed L’Étranger a lot more than I expected to. The main character half-accidentally commits a crime and is sentenced to death. He accepts the inherent absurdity of life, and finds happiness in the present moment. The closing paragraph, from the perspective of the main character who is waiting to see whether his sentence appeal will go through, includes one of my favorite quotes:

“Gazing up at the dark sky spangled with its signs and stars, for the first time, the first, I laid my heart open to the benign indifference of the universe. To feel it so like myself, indeed, so brotherly, made me realize that I’d been happy, and that I was happy still.”

I found that absurdist literature sees the world quite similarly to how I see it, with some exceptions (for example, I’m not sure I would ever want to consider the universe fully indifferent. I don’t think I’ve yet found any philosophical school of thought that I fully agree with, but I’m addressing absurdism here because this aspect of it hit close to home). To me, what many people look for in life's “meaning” or “purpose”, has always been found in simple things: the daily coffee at my house; reading a book that makes me feel things; having a good conversation with someone whose company I enjoy; feeling the sun on my skin; having the first bite of some great food; seeing the warm orange lights at a jazz bar; and so much more. These things are simple but they are huge. It was always hard to put into words for me in the past, when people desperately spoke of seeking some higher meaning, but in absurdist literature I understood that my focus has been in the present moment and the meaning created within it, and that’s what makes the difference. But of course, that’s not always easy at all. We’ll get to that in a second.

This is also why I really love Japan. It was in Japan where I encountered the most meticulous attention to detail and the most careful consideration of small, mundane things. It was there that I met a barista that was living in the small quiet town of Kanazawa, operating a tiny cafe out of his garage, and taking over 5 minutes to make a single coffee, because of how attentively he did it. He barely spoke; but Japanese jazz was playing at his cafe, and it felt infused with the greatest sense of peace and calm. I remember thinking to myself “If I ever write a book, this guy has to be a character in it”.

Like most people, I sometimes struggle to let go of experiences that offered me a welcome explosion of presence and life. Knowing you can’t relive something and clinging on to it is an entirely human experience. I’m happy now to be realizing the fact that those life experiences alone can at times be enough for one to be happy; that every small moment, detail, and feeling experienced, is worth it as it is. Even if that’s often incredibly difficult to actually internalize when you’re a person that feels everything deeply. As Camus says time and time again in The Myth of Sisyphus, one of the only things we know for certain is the consistency of human yearning and nostalgia. He’s right. Nostalgia and yearning are also very beautiful emotions in their own way, and I’m glad we experience them — they can make us lose sight of the present moment and pull us back to it with their force at the same time. Such experiences, but also the daily mundane moments of drinking coffee, reading, and creating, make up life. The key is to notice and to allow yourself to feel, that is life. Observing the rain, feeling inspired because of a poem, or even feeling desperate with yearning and confusion: these are the pieces of a puzzle that makes up a meaningful life experience. I think that especially if you’re a little predisposed to optimism you can internalize this and hopefully benefit from how liberating it is. I haven’t always been like this, far from it; but in the past few years my philosophy of life has come closer and closer to this, and I think it’s a liberating way to be.

I don’t know if anyone else feels this way, but if you do, let me know - I’d absolutely love to chat with anyone who has thoughts on the topic. Thank you so much for reading 💙

— Erifili